The Roadsworth interview - part one of four

Howdy!

Back in November, 2004 L'affaire Roadsworth began, it seems to have come to a conclusion recently with Peter Gibson's community service being the subject of an article in Le Devoir this week. Back when this was all happening, Mr. Gibson risked serious repercussions, and came to Zeke's Gallery for a rather long and extended interview. He had been prevented by the Montréal police from stepping foot in the borough of the Plateau (imagine trying to live here, and not being allowed to be in an area from Parc Ave to Papineau, Sherbrooke to Van Horne). None the less, he successfully made it into the gallery without being arrested again, and we were able to record the proceedings. If you'd like to listen along, click here [41:45 minutes, 40.1 MB] I've chopped it up into four parts. Part Two, Part Three and Part Four, are all available by clicking on the links. If you have no idea what I'm talking about, try these two links to get up to speed: one and two.

First I'd also like to thank Jacqueline Mabey, she did an amazing and wonderful job of transcribing the interview. It started out at 20,915 words, and 2:43 hours in length, then a super spectacular job of editing was done by Stephanie McLean. So it ends up at 17, 656 words, or the equivalent of a short novel. I guess that it took about 80 hours worth of work to get it into this form, and I would like to thank both of them profusely and sincerely. I'd also like to thank Urbania Magazine for kind use of their photos (Peter took a bunch as well), and finally I'd like to thank Peter for agreeing to be interviewed.

Part 1

Zeke: Let's start at the beginning. When did you start doing art?

Peter Gibson: When did I start doing art? Well, depends on what you consider art, but I've been a musician... but I guess we're talking about visual art.

Zeke: You can talk about any art.

Peter Gibson: Well, I've been a musician most of my life or, at least, since I've been trying to make a living.

Zeke: What bands have you been in? Any worth naming?

Peter Gibson: Most recently Ark of Infinity, which no longer exists. I always have a hard time... Kalmunity, recently... I always have a hard time saying those names with a straight face, for some reason [laughs]. But recently, mostly jazz, playing in jazz trios and stuff. I have been or have thought of myself as a frustrated musician, on a certain level, just because, I don't know, various reasons I won't delve into I guess. I guess in terms of visual art I never really got into it. This street project that I've been involved in lately is sort of, I guess, what got me into the visual realm. However, I had taken art classes in high school and my mom's an artist and I drew a lot as a kid and stuff like that. And we always had artistic people in and out of my house growing up. My mother always had friends over. So that's kind of an artistic background. But as far as physically engaging myself in the visual art realm, it's really only been in the last three or four years, with a few exceptions here and there.

Zeke: And was there a specific time - what I like calling the Eureka Moment - that switched you over?

Peter Gibson: Yeah, the Eureka Moment for me, so to speak, was - like I said, I've always been into music, and I got into homestyle production with computers and samplers and stuff like that. And part of what appealed to me about that was its visual aspect. To me, I related the experience of working with a sampler and working with sequencers and software almost as a painterly type experience, there's a painterly, visual, sensual aspect about that kind of musical production, for me.

Zeke: Yeah, when I record - my girlfriend mentioned it - the wave forms as they're put up on the screen, they're like pulling out scenes for movies. "Hey, that looks like a recording! That looks like the band that played!" And I'm saying, "Hello? Oh, I get it!"

Peter Gibson: Yeah, that's it, exactly. It's got... it's undeniable the visual and aural connection. And both sides have sort of informed my interests, my sort of artistic endeavors, if you will.

Zeke: So, then, did you start out straight to stencil?

Peter Gibson: Well, the Eureka Moment, as you put it, would be my girlfriend showed me a book of - I've mentioned it a few times - of this artist, Andy Goldsworthy, who you've probably heard of.

Zeke: Yes.

Peter Gibson: He's what people often refer to as a landscape artist, art. I guess it's a movement that's been around... I'm not really aware of landscape art as a movement.

Zeke: There, once these legal difficulties get settled, get your ass down to this place called Dia Beacon in New York. It's this place, basically museum/gallery, they sort of turn the concept of museum on its head, where museum, bam! you put in art to then designate "This is canon, this is art," serious. They went the other way around, and said, "You artist, you artist, you artist, are worthy of stuff. We then are going to build a space for you so as to preserve your stuff." They started with a space in New York. But there, "Spiral Jetty," out in Salt Lake City, Marfa - both of these are specific artists who did entire... they are the ones who did get scads of money and took over a large Nabisco factory in Beacon, New York, which is about an hour outside of New York City.

Peter Gibson: I think I've heard of that.

Zeke: And they have Richard Serras up the wazoo, and considering each Richard Serra is about a gazillion tons, you suddenly come across 17 of them and say whoa. And Michael Govan who runs it is an absolutely phenomenal guy. And at which point they have tons of land art. And they have about a dozen artists that they say, "Whatever you do, however you do it" - because there is this one guy who's come up with a dome in the desert, that has a hole in the center, and that's the art piece. "So I'm looking at the color of the sky, it's changing, cool shit!" Or like the lightning field in New Mexico, where they have the rods and you go out and watch the lightning. It is the sort of thing where Dia, which is the organization responsible, is saying, "We will preserve these, a museum does not need four walls." Dia Beacon is there sort of saying, "Yeah, four walls do make it real easy to charge admission, to keep track of stuff, to make sure the administrative functions can get done," and so on. But yeah, I highly, highly recommend it.

Peter Gibson: Cool. Dia Beacon?

Zeke: Yeah, Dia in New York as well, which is Dia Chelsea. Yeah, if you want I can give you more information.

Peter Gibson: Definitely.

Zeke: But that is more as an aside. We're here to hear you talking.

Peter Gibson: Well, it's not really an aside, because you raised an important question, that desire to get away from - or not necessarily a desire but a possibility of getting away from - the four walls, the charging of admission, the whole museum concept which is obviously not a new concept.

Zeke: Relatively.

Peter Gibson: Relatively within the canon of art history, it's a new concept. I guess there's still some territory to explore, because people are still interested in that side of things. But, for me, going back to Andy Goldsworthy, just seeing his work there was something very, on the one hand, very childlike but, on the other hand, very sophisticated and elegant about his work that I found very exciting.

Zeke: Have you ever tried to contact him?

Peter Gibson: No, I haven't.

Zeke: I wouldn't expect so, but given my nature, it's "Hello, you're a wonderful guy, can I get an autograph?"

Peter Gibson: Yeah, totally, I'd love to meet him. I've seen that movie of his. If you look at what I've done and what he does you wouldn't necessarily see the relationship.

Zeke: I can see the relationship, but I didn't think of it until you started mentioning him. I can see how one leads into the other. Once you finish I will come in with a question so you can actually explain to me how….

Peter Gibson: OK, cool. Well, exactly, I had this Eureka Moment, when I saw this artwork and I actually went on the roof of my house and started playing with shadows, with the stones. I kinda went off and my girlfriend kinda freaked out. She was wondering where I was and saw me on the roof, playing with rubble, and I think she was a little disturbed; it was one of those moments, one of those psycho moments.

Zeke: You need to be able to explain yourself thoroughly.

Peter Gibson: Yeah, that's what I'm finding, that's the tricky part. It's one thing to do something, but to actually back it up in a coherent manner is...

Zeke: That's one thing I find ridiculous: with the whole grant culture we have here, getting artists to write about what they're doing - hello, they're not writers!

Peter Gibson: That's the whole point, that's why we're doing art, in a sense. It's the old saying, "You can't dance about architecture."

Zeke: To my mind, you can, but dancing about architecture requires a comprehensive knowledge about architecture. Let's get back to Andy Goldsworthy. Would you like another beer? I want another beer.

Peter Gibson: Sure.

Zeke: Or would you like bourbon?

Peter Gibson: Beer sounds good.

Zeke: OK.

Peter Gibson: Mind if I grab a smoke?

Zeke: Not at all.

Peter Gibson: So basically something that struck a cord, in his work. I sort of relate it all - as many people do - to 9/11, because it was such a pivotal moment in, at least, Western history, for a lot of people, for me in a way, maybe not personally, but sort of in terms of my global awareness, my political thinking. So it was right before that that I discovered Andrew, several months before that. And I was just trying to think - it's curious, the whole appealing thing about Andy Goldsworthy, to me, it reminded me of games you play when you're a kid in the backyard, you know, you build things, you play around, you hop fences, you play games. And just that kind of freedom and imagination that I felt I'd sort of lost to a certain extent, you know, through my adult... whatever. I felt I sort of had lost that to a certain extent, and seeing with that spirit but with a sophistication and a maturity at the same time really excited me. I was thinking: What's my backyard now? My backyard is the concrete jungle basically, so I was trying to think of ways that that spirit could be translated in an urban setting. Like, hmmm, how can I bring this to an urban setting?

Zeke: So it was a conscious effort to try and say, "OK, I want to do Andy Goldworthy-like stuff, but I want to do it in the urban environment?"

Peter Gibson: Well, kind of, yeah. Obviously not so literally, because if you look at what I do the connection is more abstract in the actual result.

Zeke: I've only seen two pictures of his where he is using landscape stuff such as flowers and so on and then alter the landscape with landscape stuff, I see a very direct relation to you saying "that was what fascinated me" with the first set of stuff you did back in 2001, 2002, using the same damn paints as the city. At which point, Luci, my girlfriend, said, "That's real easy, just go out and get some concrete paint."

Peter Gibson: Yeah, exactly. It's extremely simple, that's what excited me, the simplicity of it all, and that kind of moment like, "Fuck, anybody could have done that," in a sense. Of course, there's a craft and an art and aspect of patience -

Footprint by Peter 'Roadsworth' Gibson

Zeke: In my mind, it's also an issue of thought process that nobody else has gone through. Yeah, anybody else could do that if they had gone through the same steps.

Peter Gibson: Yeah, whatever, I'm not trying to... but ah, so yeah, exactly, in the same way that Andy Goldsworthy uses elements in nature - whether they're leaves, sticks, the raw material of nature - and the way he integrates those elements into creating another sort of... well, creating art, I guess, creating a visual... another aesthetic, I guess, bringing a human element to nature, in his case, without bringing the sort of technical, industrial process to the process. Process to the process [laughs]. So I kinda viewed it in that way and thought, in a city, there are certain elements and raw materials that exist. And yes, they're all man-made, but I kinda started thinking along the lines of, what is manmade? Because we are a product of nature, although that's debatable, because there are theories that we maybe came from Mars, there are all kinds of theories... so maybe we are alien on this planet because, to a certain degree, our human processes don't seem to - at least on the scale we've developed them - don't seem to be necessarily compatible with earth, ecological systems for example. Which is debatable as well, because maybe this is just all part of the natural process..

Zeke: The grand scheme of things.

Peter Gibson: Exactly. But anyway, I started looking at that, and saying, "Well, all these products that we build, all these man-made processes come from the earth, we've bent them and forged them into new elements." But just sort of thinking on those lines, and looking at the lines on the street, the concrete, the symbols, as almost a natural element, just wanted to think how I could integrate those elements, and I guess just sort of bring them together to suggest another... to bring a poetic kind of meaning to what's, in general, in the city, a very utilitarian.…

Zeke: Well, you succeeded immensely.

Peter Gibson: Well, that was the idea. And that's where I think Andy Goldsworthy, bringing poetry to the wildness of nature, to the lawlessness. And I feel there's a certain lawlessness to cities as well, even though there are controls in place, there is a lawless element. It all goes back to this whole debate people have about vandalism and graffiti and all these things. And I personally look at graffiti almost as - I know I'm supposed to be officially distancing myself from the graffiti world - but, it's natural sort of by product of human activity. Just like cars and pollution and concrete and advertising, and all this shit around us, and to me it's the least offensive of these things. I don't know why people are so focused... why their hatred is so focused on it.

Zeke: You see my doorway?

Peter Gibson: Yeah, it's covered.

Zeke: I'm not terribly happy about it.

Peter Gibson: No, I understand, but it seems - and this is my view - a little hypocritical that we get so upset about that on our doorways, and yet have no problem that there is a car parked in front of our driveway spewing shit into the air and blackening your facade.

Zeke: No, I'm just as pissed off there, but it is, to me - I come with a slightly finer line - in that, the graffiti, when done well, and at which point some 16-year-old kid saying, "Hello?! I exist." I don't need that. If you want to tell me you exist, walk up the damn stairs, say, "Hi, how you doing?" I'll offer you coffee, I'll offer you beer.

Peter Gibson: Fair enough, but look at the environment these 16-year-old kids are saying "I exist" in. They're saying it in an environment where there are hundreds of other elements - advertising, to use one example, signs, property. Just the fact that you own property, you're claiming, you're staking quite a big part of public space or the public domain, and you're saying "I exist." There are so many forms of saying "I exist."

VIP Rope by Peter 'Roadsworth' Gibson

Zeke: Certain ones are graceful, poetic, interesting. Other ones are…

Peter Gibson: Fair enough, fair enough.

Zeke: In terms of Marc Lepine saying, "I exist," I'm not a big fan of how he pulled that off.

Peter Gibson: Fair enough. I agree with you.

Zeke: To then lump good and bad saying "I exist" together, I understand what you're saying, I think, but I don't agree with it. I think that everybody should have the right, but everybody should be saying, "What I can I be doing positively?" What can I do - if it's not positive - let's make it be poetic, let's make it interesting. My way of existence is different from somebody else's, as opposed to me shitting on their doorstep. How can I do it in such a way so that they then realize what they're doing is bad, and that's why I'm against the tags.

Peter Gibson: I agree with you, but what gets me is the hypocrisy. Fair enough, maybe it's not aesthetically pleasing, maybe it's ego-driven, maybe it's defacing public property, but in my opinion, there are a lot more harmful ways of saying "I exist" and people do it in accepted - it's a very accepted form. A car is a form of dress, it's kinda like the clothes you wear. But there, it's a very intrusive form in a sense, in my opinion, of saying, "This is my style, this is my vibe, I'm cool."

Zeke: That's one of my favorite things, when people come in here, say "Do you recycle?" And I say, "I don't need to." And they say, "Huh?" At which point, I say, "I've never owned a car, don't know how to drive. I'm doing more for the damn planet than recycling could ever do. Get off my damn case about recycling, I don't want three garbage cans."

Peter Gibson: Well, this is the thing: I don't think anyone is perfect. It's very hard to... I mean, we all have ideals and morals and ideas about positive contributions to society or to ourselves. Because I think it comes down to, if you realize that we're all in this together, and that's one of the sort of realizations I had with the 9/11 scenario, I mean I realized it before but... if you realize that your personal contribution, whether it's a contribution to your community or environment or society, is a contribution to yourself as well. It sounds kind of corny, maybe -

Zeke: It still works.

Peter Gibson: But on that note, what bugs me, is people, yeah, have a point, there is a lot of moral... but when people get really self-righteous about, for example, graffiti, you know, but meanwhile they're viewing this landscape, this sort of aesthetically displeasing landscape on their way to work, in some cases, one end of the city to the other, they're viewing this through their tinted glass window, so many people use the city as transitional space. They don't invest in that city. And I think a lot of it has to do with how we get around the city, the way the city's designed, the way we move about the city. If you don't own a car or don't have a license - I'm not dissing people that do - but you have more an appreciation for space, in general, if you ride a bike. There's a physical connection between going from Point A to Point B. It's not some sort of virtual...

Zeke: Yeah, to me, it was wonderful, when the bailiff showed up, and said, "I need a certified cheque." I said, "OK, give me five minutes." He said, "Yeah, no problem, I'll go to the bank with you." I said, "Yeah, no problem, whatever." And he went to his car! And I'm saying, "Hello? It's two minutes down the road!" I went to the bank, took 15 minutes to get the damn certified cheque, waited another 15 minutes, and he still hadn't shown up [laughs]!

Peter Gibson: Yeah, for me it was the same thing. I went there on my bike, and I got there before, and it's the other side of town. Anyway, that hypocrisy was part of what inspired me to also want to... I mean, yes, there's that purely sensual, visual excitement and, I guess, that intellectual - I don't know what you want to call it - aesthetic exercise of trying to translate this Andy Goldsworthy inspiration. I don't think that's the only inspiration, but that's the one that most consciously comes to mind. There's that excitement. There's also... a certain amount of it was a reaction to my getting started on stencils and public art, which is what it's being called, although I've been uncomfortable...

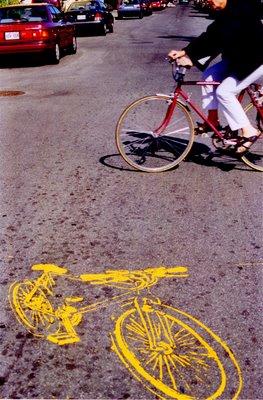

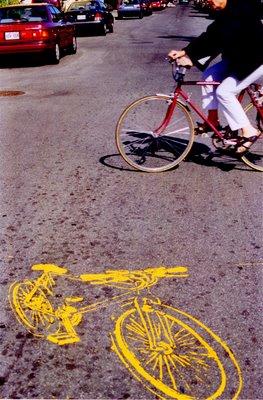

Bike Path 2 by Peter 'Roadsworth' Gibson

Zeke: What would you call it?

Peter Gibson: Well, no, I would call it that -

Zeke: Then why are you uncomfortable?

Peter Gibson: I've always been uncomfortable with the term "art," for some reason. And I think it has to do with my own standards regarding art and what art should be. And I guess they're very high, so I guess part of me feels... it always feels like a pretentious label to me, though I'm getting use to it now, just because it's been applied to what I've done. But I guess that whole definition of what art is, I guess I'm just uncomfortable… again, going back to what we were saying, advertising, wherein a lot of artistic ability goes into the creation of it. By the same token, there's stuff that's called "art" that I find extremely boring and dull, almost on par with a marketing sensibility, in the sense that it's very aware, there's a lot of politics... the whole term "art," to me, in this day and age, is very nebulous, it seems to have so many... I guess it's like "love," [laughs] what is that? I guess I have a hard time.…

Zeke: You still together with your girlfriend?

Peter Gibson: Yes, of course.

Zeke: To me, to my mind - I had this talk with a friend - my definition of art is that if it makes you think, it is art.

Peter Gibson: Yeah, but everything makes you think.

Zeke: No, no, no.

Peter Gibson: Makes you think on different levels, makes you think.

Zeke: No, right now you are not thinking about the color of my walls.

Peter Gibson: True.

Zeke: But now that I brought it up, now you're thinking. If, previously, my walls were such -

Peter Gibson: But I'm not thinking about that object d'art in front of me.

Zeke: If you were to focus in on it, and look at it, you could then see the graphic of the green wall behind you and focus in on the artistic qualities of it and so on. And if you're not thinking, it's not art, if you are thinking it is art. To me, what makes wonderful art, that object d'art behind you, one thing is it's nice, but it doesn't grab you by the short and curlies. Great art will stop you dead in your tracks, and will say, "Hello! Look at me, concentrate, think." Bad art will say, "Oh, I happen to be in front of you," I can think about it, but once I'm gone, it's gone from memory.

Peter Gibson: That's a good definition.

Zeke: Easy litmus test for me in terms of if it's good art, three months after the fact, can I remember what it looked like and so on.

Peter Gibson: Hey, I'll take that definition as good to me. I'm not saying there isn't a definition for art, and I'm not saying other people's definitions aren't... I'm just saying I've felt uncomfortable with it for some reason because, at the same time, it seems - and again, this is my own feelings - but it seems as though there is this notion of purity attached to art and the artist and this snowy white purity...

Zeke: Have you ever seen the buttons I have for the gallery?

Peter Gibson: No, I haven't.

Zeke: I'll show you one.

Peter Gibson: That kind of strikes me in a hypocritical way, in the same way that people are so pure about their city and not having kids mark their precious walls and yet we have no problem fuckin' erecting these atrocities, these eyesores everywhere, and nobody says anything - well, people do, people do say things.

Zeke: Well, not everybody.

Peter Gibson: Not everybody. Anyway, it seems like a... anyway, to get away from, that's a side sort of issue. That level of hypocrisy went hand-in-hand with that sort of pure artistic, expressive sort of pleasure of that. And this started September 11th. And the other reason I say that I don't necessarily immediately associate my stuff to art is because the first stencil I did was a bike. I mean, I'm a cyclist.

Zeke: Uh huh, right down on the corner of St-Dominique and Napoleon.

Peter Gibson: Yeah, there was one, that was one. I did one before that that was...

Zeke: Oh, I'm recognizing the stencil, was that the first stencil?

Peter Gibson: No, no. That wasn't the first one, but there was another stencil that I did. But yeah, I did that one later. That's more perspective. But I did one before like that which was trying to mimic the city's language, you know, at the bike paths they have the circles.

Back in November, 2004 L'affaire Roadsworth began, it seems to have come to a conclusion recently with Peter Gibson's community service being the subject of an article in Le Devoir this week. Back when this was all happening, Mr. Gibson risked serious repercussions, and came to Zeke's Gallery for a rather long and extended interview. He had been prevented by the Montréal police from stepping foot in the borough of the Plateau (imagine trying to live here, and not being allowed to be in an area from Parc Ave to Papineau, Sherbrooke to Van Horne). None the less, he successfully made it into the gallery without being arrested again, and we were able to record the proceedings. If you'd like to listen along, click here [41:45 minutes, 40.1 MB] I've chopped it up into four parts. Part Two, Part Three and Part Four, are all available by clicking on the links. If you have no idea what I'm talking about, try these two links to get up to speed: one and two.

First I'd also like to thank Jacqueline Mabey, she did an amazing and wonderful job of transcribing the interview. It started out at 20,915 words, and 2:43 hours in length, then a super spectacular job of editing was done by Stephanie McLean. So it ends up at 17, 656 words, or the equivalent of a short novel. I guess that it took about 80 hours worth of work to get it into this form, and I would like to thank both of them profusely and sincerely. I'd also like to thank Urbania Magazine for kind use of their photos (Peter took a bunch as well), and finally I'd like to thank Peter for agreeing to be interviewed.

Part 1

Zeke: Let's start at the beginning. When did you start doing art?

Peter Gibson: When did I start doing art? Well, depends on what you consider art, but I've been a musician... but I guess we're talking about visual art.

Zeke: You can talk about any art.

Peter Gibson: Well, I've been a musician most of my life or, at least, since I've been trying to make a living.

Zeke: What bands have you been in? Any worth naming?

Peter Gibson: Most recently Ark of Infinity, which no longer exists. I always have a hard time... Kalmunity, recently... I always have a hard time saying those names with a straight face, for some reason [laughs]. But recently, mostly jazz, playing in jazz trios and stuff. I have been or have thought of myself as a frustrated musician, on a certain level, just because, I don't know, various reasons I won't delve into I guess. I guess in terms of visual art I never really got into it. This street project that I've been involved in lately is sort of, I guess, what got me into the visual realm. However, I had taken art classes in high school and my mom's an artist and I drew a lot as a kid and stuff like that. And we always had artistic people in and out of my house growing up. My mother always had friends over. So that's kind of an artistic background. But as far as physically engaging myself in the visual art realm, it's really only been in the last three or four years, with a few exceptions here and there.

Zeke: And was there a specific time - what I like calling the Eureka Moment - that switched you over?

Peter Gibson: Yeah, the Eureka Moment for me, so to speak, was - like I said, I've always been into music, and I got into homestyle production with computers and samplers and stuff like that. And part of what appealed to me about that was its visual aspect. To me, I related the experience of working with a sampler and working with sequencers and software almost as a painterly type experience, there's a painterly, visual, sensual aspect about that kind of musical production, for me.

Zeke: Yeah, when I record - my girlfriend mentioned it - the wave forms as they're put up on the screen, they're like pulling out scenes for movies. "Hey, that looks like a recording! That looks like the band that played!" And I'm saying, "Hello? Oh, I get it!"

Peter Gibson: Yeah, that's it, exactly. It's got... it's undeniable the visual and aural connection. And both sides have sort of informed my interests, my sort of artistic endeavors, if you will.

Zeke: So, then, did you start out straight to stencil?

Peter Gibson: Well, the Eureka Moment, as you put it, would be my girlfriend showed me a book of - I've mentioned it a few times - of this artist, Andy Goldsworthy, who you've probably heard of.

Zeke: Yes.

Peter Gibson: He's what people often refer to as a landscape artist, art. I guess it's a movement that's been around... I'm not really aware of landscape art as a movement.

Zeke: There, once these legal difficulties get settled, get your ass down to this place called Dia Beacon in New York. It's this place, basically museum/gallery, they sort of turn the concept of museum on its head, where museum, bam! you put in art to then designate "This is canon, this is art," serious. They went the other way around, and said, "You artist, you artist, you artist, are worthy of stuff. We then are going to build a space for you so as to preserve your stuff." They started with a space in New York. But there, "Spiral Jetty," out in Salt Lake City, Marfa - both of these are specific artists who did entire... they are the ones who did get scads of money and took over a large Nabisco factory in Beacon, New York, which is about an hour outside of New York City.

Peter Gibson: I think I've heard of that.

Zeke: And they have Richard Serras up the wazoo, and considering each Richard Serra is about a gazillion tons, you suddenly come across 17 of them and say whoa. And Michael Govan who runs it is an absolutely phenomenal guy. And at which point they have tons of land art. And they have about a dozen artists that they say, "Whatever you do, however you do it" - because there is this one guy who's come up with a dome in the desert, that has a hole in the center, and that's the art piece. "So I'm looking at the color of the sky, it's changing, cool shit!" Or like the lightning field in New Mexico, where they have the rods and you go out and watch the lightning. It is the sort of thing where Dia, which is the organization responsible, is saying, "We will preserve these, a museum does not need four walls." Dia Beacon is there sort of saying, "Yeah, four walls do make it real easy to charge admission, to keep track of stuff, to make sure the administrative functions can get done," and so on. But yeah, I highly, highly recommend it.

Peter Gibson: Cool. Dia Beacon?

Zeke: Yeah, Dia in New York as well, which is Dia Chelsea. Yeah, if you want I can give you more information.

Peter Gibson: Definitely.

Zeke: But that is more as an aside. We're here to hear you talking.

Peter Gibson: Well, it's not really an aside, because you raised an important question, that desire to get away from - or not necessarily a desire but a possibility of getting away from - the four walls, the charging of admission, the whole museum concept which is obviously not a new concept.

Zeke: Relatively.

Peter Gibson: Relatively within the canon of art history, it's a new concept. I guess there's still some territory to explore, because people are still interested in that side of things. But, for me, going back to Andy Goldsworthy, just seeing his work there was something very, on the one hand, very childlike but, on the other hand, very sophisticated and elegant about his work that I found very exciting.

Zeke: Have you ever tried to contact him?

Peter Gibson: No, I haven't.

Zeke: I wouldn't expect so, but given my nature, it's "Hello, you're a wonderful guy, can I get an autograph?"

Peter Gibson: Yeah, totally, I'd love to meet him. I've seen that movie of his. If you look at what I've done and what he does you wouldn't necessarily see the relationship.

Zeke: I can see the relationship, but I didn't think of it until you started mentioning him. I can see how one leads into the other. Once you finish I will come in with a question so you can actually explain to me how….

Peter Gibson: OK, cool. Well, exactly, I had this Eureka Moment, when I saw this artwork and I actually went on the roof of my house and started playing with shadows, with the stones. I kinda went off and my girlfriend kinda freaked out. She was wondering where I was and saw me on the roof, playing with rubble, and I think she was a little disturbed; it was one of those moments, one of those psycho moments.

Zeke: You need to be able to explain yourself thoroughly.

Peter Gibson: Yeah, that's what I'm finding, that's the tricky part. It's one thing to do something, but to actually back it up in a coherent manner is...

Zeke: That's one thing I find ridiculous: with the whole grant culture we have here, getting artists to write about what they're doing - hello, they're not writers!

Peter Gibson: That's the whole point, that's why we're doing art, in a sense. It's the old saying, "You can't dance about architecture."

Zeke: To my mind, you can, but dancing about architecture requires a comprehensive knowledge about architecture. Let's get back to Andy Goldsworthy. Would you like another beer? I want another beer.

Peter Gibson: Sure.

Zeke: Or would you like bourbon?

Peter Gibson: Beer sounds good.

Zeke: OK.

Peter Gibson: Mind if I grab a smoke?

Zeke: Not at all.

Peter Gibson: So basically something that struck a cord, in his work. I sort of relate it all - as many people do - to 9/11, because it was such a pivotal moment in, at least, Western history, for a lot of people, for me in a way, maybe not personally, but sort of in terms of my global awareness, my political thinking. So it was right before that that I discovered Andrew, several months before that. And I was just trying to think - it's curious, the whole appealing thing about Andy Goldsworthy, to me, it reminded me of games you play when you're a kid in the backyard, you know, you build things, you play around, you hop fences, you play games. And just that kind of freedom and imagination that I felt I'd sort of lost to a certain extent, you know, through my adult... whatever. I felt I sort of had lost that to a certain extent, and seeing with that spirit but with a sophistication and a maturity at the same time really excited me. I was thinking: What's my backyard now? My backyard is the concrete jungle basically, so I was trying to think of ways that that spirit could be translated in an urban setting. Like, hmmm, how can I bring this to an urban setting?

Zeke: So it was a conscious effort to try and say, "OK, I want to do Andy Goldworthy-like stuff, but I want to do it in the urban environment?"

Peter Gibson: Well, kind of, yeah. Obviously not so literally, because if you look at what I do the connection is more abstract in the actual result.

Zeke: I've only seen two pictures of his where he is using landscape stuff such as flowers and so on and then alter the landscape with landscape stuff, I see a very direct relation to you saying "that was what fascinated me" with the first set of stuff you did back in 2001, 2002, using the same damn paints as the city. At which point, Luci, my girlfriend, said, "That's real easy, just go out and get some concrete paint."

Peter Gibson: Yeah, exactly. It's extremely simple, that's what excited me, the simplicity of it all, and that kind of moment like, "Fuck, anybody could have done that," in a sense. Of course, there's a craft and an art and aspect of patience -

Footprint by Peter 'Roadsworth' Gibson

Zeke: In my mind, it's also an issue of thought process that nobody else has gone through. Yeah, anybody else could do that if they had gone through the same steps.

Peter Gibson: Yeah, whatever, I'm not trying to... but ah, so yeah, exactly, in the same way that Andy Goldsworthy uses elements in nature - whether they're leaves, sticks, the raw material of nature - and the way he integrates those elements into creating another sort of... well, creating art, I guess, creating a visual... another aesthetic, I guess, bringing a human element to nature, in his case, without bringing the sort of technical, industrial process to the process. Process to the process [laughs]. So I kinda viewed it in that way and thought, in a city, there are certain elements and raw materials that exist. And yes, they're all man-made, but I kinda started thinking along the lines of, what is manmade? Because we are a product of nature, although that's debatable, because there are theories that we maybe came from Mars, there are all kinds of theories... so maybe we are alien on this planet because, to a certain degree, our human processes don't seem to - at least on the scale we've developed them - don't seem to be necessarily compatible with earth, ecological systems for example. Which is debatable as well, because maybe this is just all part of the natural process..

Zeke: The grand scheme of things.

Peter Gibson: Exactly. But anyway, I started looking at that, and saying, "Well, all these products that we build, all these man-made processes come from the earth, we've bent them and forged them into new elements." But just sort of thinking on those lines, and looking at the lines on the street, the concrete, the symbols, as almost a natural element, just wanted to think how I could integrate those elements, and I guess just sort of bring them together to suggest another... to bring a poetic kind of meaning to what's, in general, in the city, a very utilitarian.…

Zeke: Well, you succeeded immensely.

Peter Gibson: Well, that was the idea. And that's where I think Andy Goldsworthy, bringing poetry to the wildness of nature, to the lawlessness. And I feel there's a certain lawlessness to cities as well, even though there are controls in place, there is a lawless element. It all goes back to this whole debate people have about vandalism and graffiti and all these things. And I personally look at graffiti almost as - I know I'm supposed to be officially distancing myself from the graffiti world - but, it's natural sort of by product of human activity. Just like cars and pollution and concrete and advertising, and all this shit around us, and to me it's the least offensive of these things. I don't know why people are so focused... why their hatred is so focused on it.

Zeke: You see my doorway?

Peter Gibson: Yeah, it's covered.

Zeke: I'm not terribly happy about it.

Peter Gibson: No, I understand, but it seems - and this is my view - a little hypocritical that we get so upset about that on our doorways, and yet have no problem that there is a car parked in front of our driveway spewing shit into the air and blackening your facade.

Zeke: No, I'm just as pissed off there, but it is, to me - I come with a slightly finer line - in that, the graffiti, when done well, and at which point some 16-year-old kid saying, "Hello?! I exist." I don't need that. If you want to tell me you exist, walk up the damn stairs, say, "Hi, how you doing?" I'll offer you coffee, I'll offer you beer.

Peter Gibson: Fair enough, but look at the environment these 16-year-old kids are saying "I exist" in. They're saying it in an environment where there are hundreds of other elements - advertising, to use one example, signs, property. Just the fact that you own property, you're claiming, you're staking quite a big part of public space or the public domain, and you're saying "I exist." There are so many forms of saying "I exist."

VIP Rope by Peter 'Roadsworth' Gibson

Zeke: Certain ones are graceful, poetic, interesting. Other ones are…

Peter Gibson: Fair enough, fair enough.

Zeke: In terms of Marc Lepine saying, "I exist," I'm not a big fan of how he pulled that off.

Peter Gibson: Fair enough. I agree with you.

Zeke: To then lump good and bad saying "I exist" together, I understand what you're saying, I think, but I don't agree with it. I think that everybody should have the right, but everybody should be saying, "What I can I be doing positively?" What can I do - if it's not positive - let's make it be poetic, let's make it interesting. My way of existence is different from somebody else's, as opposed to me shitting on their doorstep. How can I do it in such a way so that they then realize what they're doing is bad, and that's why I'm against the tags.

Peter Gibson: I agree with you, but what gets me is the hypocrisy. Fair enough, maybe it's not aesthetically pleasing, maybe it's ego-driven, maybe it's defacing public property, but in my opinion, there are a lot more harmful ways of saying "I exist" and people do it in accepted - it's a very accepted form. A car is a form of dress, it's kinda like the clothes you wear. But there, it's a very intrusive form in a sense, in my opinion, of saying, "This is my style, this is my vibe, I'm cool."

Zeke: That's one of my favorite things, when people come in here, say "Do you recycle?" And I say, "I don't need to." And they say, "Huh?" At which point, I say, "I've never owned a car, don't know how to drive. I'm doing more for the damn planet than recycling could ever do. Get off my damn case about recycling, I don't want three garbage cans."

Peter Gibson: Well, this is the thing: I don't think anyone is perfect. It's very hard to... I mean, we all have ideals and morals and ideas about positive contributions to society or to ourselves. Because I think it comes down to, if you realize that we're all in this together, and that's one of the sort of realizations I had with the 9/11 scenario, I mean I realized it before but... if you realize that your personal contribution, whether it's a contribution to your community or environment or society, is a contribution to yourself as well. It sounds kind of corny, maybe -

Zeke: It still works.

Peter Gibson: But on that note, what bugs me, is people, yeah, have a point, there is a lot of moral... but when people get really self-righteous about, for example, graffiti, you know, but meanwhile they're viewing this landscape, this sort of aesthetically displeasing landscape on their way to work, in some cases, one end of the city to the other, they're viewing this through their tinted glass window, so many people use the city as transitional space. They don't invest in that city. And I think a lot of it has to do with how we get around the city, the way the city's designed, the way we move about the city. If you don't own a car or don't have a license - I'm not dissing people that do - but you have more an appreciation for space, in general, if you ride a bike. There's a physical connection between going from Point A to Point B. It's not some sort of virtual...

Zeke: Yeah, to me, it was wonderful, when the bailiff showed up, and said, "I need a certified cheque." I said, "OK, give me five minutes." He said, "Yeah, no problem, I'll go to the bank with you." I said, "Yeah, no problem, whatever." And he went to his car! And I'm saying, "Hello? It's two minutes down the road!" I went to the bank, took 15 minutes to get the damn certified cheque, waited another 15 minutes, and he still hadn't shown up [laughs]!

Peter Gibson: Yeah, for me it was the same thing. I went there on my bike, and I got there before, and it's the other side of town. Anyway, that hypocrisy was part of what inspired me to also want to... I mean, yes, there's that purely sensual, visual excitement and, I guess, that intellectual - I don't know what you want to call it - aesthetic exercise of trying to translate this Andy Goldsworthy inspiration. I don't think that's the only inspiration, but that's the one that most consciously comes to mind. There's that excitement. There's also... a certain amount of it was a reaction to my getting started on stencils and public art, which is what it's being called, although I've been uncomfortable...

Bike Path 2 by Peter 'Roadsworth' Gibson

Zeke: What would you call it?

Peter Gibson: Well, no, I would call it that -

Zeke: Then why are you uncomfortable?

Peter Gibson: I've always been uncomfortable with the term "art," for some reason. And I think it has to do with my own standards regarding art and what art should be. And I guess they're very high, so I guess part of me feels... it always feels like a pretentious label to me, though I'm getting use to it now, just because it's been applied to what I've done. But I guess that whole definition of what art is, I guess I'm just uncomfortable… again, going back to what we were saying, advertising, wherein a lot of artistic ability goes into the creation of it. By the same token, there's stuff that's called "art" that I find extremely boring and dull, almost on par with a marketing sensibility, in the sense that it's very aware, there's a lot of politics... the whole term "art," to me, in this day and age, is very nebulous, it seems to have so many... I guess it's like "love," [laughs] what is that? I guess I have a hard time.…

Zeke: You still together with your girlfriend?

Peter Gibson: Yes, of course.

Zeke: To me, to my mind - I had this talk with a friend - my definition of art is that if it makes you think, it is art.

Peter Gibson: Yeah, but everything makes you think.

Zeke: No, no, no.

Peter Gibson: Makes you think on different levels, makes you think.

Zeke: No, right now you are not thinking about the color of my walls.

Peter Gibson: True.

Zeke: But now that I brought it up, now you're thinking. If, previously, my walls were such -

Peter Gibson: But I'm not thinking about that object d'art in front of me.

Zeke: If you were to focus in on it, and look at it, you could then see the graphic of the green wall behind you and focus in on the artistic qualities of it and so on. And if you're not thinking, it's not art, if you are thinking it is art. To me, what makes wonderful art, that object d'art behind you, one thing is it's nice, but it doesn't grab you by the short and curlies. Great art will stop you dead in your tracks, and will say, "Hello! Look at me, concentrate, think." Bad art will say, "Oh, I happen to be in front of you," I can think about it, but once I'm gone, it's gone from memory.

Peter Gibson: That's a good definition.

Zeke: Easy litmus test for me in terms of if it's good art, three months after the fact, can I remember what it looked like and so on.

Peter Gibson: Hey, I'll take that definition as good to me. I'm not saying there isn't a definition for art, and I'm not saying other people's definitions aren't... I'm just saying I've felt uncomfortable with it for some reason because, at the same time, it seems - and again, this is my own feelings - but it seems as though there is this notion of purity attached to art and the artist and this snowy white purity...

Zeke: Have you ever seen the buttons I have for the gallery?

Peter Gibson: No, I haven't.

Zeke: I'll show you one.

Peter Gibson: That kind of strikes me in a hypocritical way, in the same way that people are so pure about their city and not having kids mark their precious walls and yet we have no problem fuckin' erecting these atrocities, these eyesores everywhere, and nobody says anything - well, people do, people do say things.

Zeke: Well, not everybody.

Peter Gibson: Not everybody. Anyway, it seems like a... anyway, to get away from, that's a side sort of issue. That level of hypocrisy went hand-in-hand with that sort of pure artistic, expressive sort of pleasure of that. And this started September 11th. And the other reason I say that I don't necessarily immediately associate my stuff to art is because the first stencil I did was a bike. I mean, I'm a cyclist.

Zeke: Uh huh, right down on the corner of St-Dominique and Napoleon.

Peter Gibson: Yeah, there was one, that was one. I did one before that that was...

Zeke: Oh, I'm recognizing the stencil, was that the first stencil?

Peter Gibson: No, no. That wasn't the first one, but there was another stencil that I did. But yeah, I did that one later. That's more perspective. But I did one before like that which was trying to mimic the city's language, you know, at the bike paths they have the circles.

<< Home