The Jean-François Lacombe Interview

Howdy!

Back at the end of 2004 during Jean-François Lacombe's exhibit here I interviewed him. It has finally been transcribed by Jacquline Mabey, who I thank ever so much for her help. All of the photos were taken by Paul Litherland, unless they were taken by Jean-François.

If you'd like more information about Jean-François Lacombe's work click here, or here.

Zeke: First, what do you think about the show? Don't pull any punches.

Jean-François Lacombe: Qu'est ce que tu veux dire? [What do you mean?]

Zeke: Don't hold back anything.

Jean-François Lacombe: I'm pleased about it. I'm pleased with the changes you made. I'm very pleased with the effort. The only problem is the invitations. I would have hoped that they could have been sent out earlier.

Zeke: Yeah, I agree.

Jean-François Lacombe: There would have been more people at the event. But I'm also happy about the vernisage because there were lots of people who I didn't know.

Zeke: OK. What do you have as far as plans for the future?

Jean-François Lacombe: I'm going to be applying to the Jardin de Metis. And that's a big step for me. That's the direction I'd like to go. I want to continue sculpting pieces, small pieces, for inside, in gallery. But, this would be more an interactive work, a site-specific work. And, since there's about a hundred thousand people that visit the Jardin de Metis every year it's a nice opportunity. And since it's a garden, I can interact with nature.

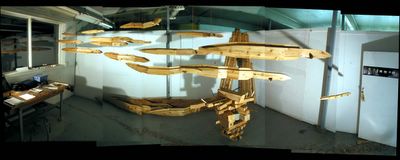

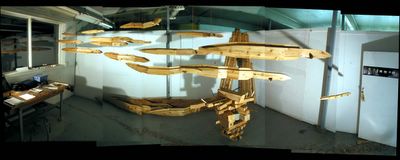

Installation Shot from Above, Below, Center and Ether

Zeke: And beyond that? Do you have any ideas, plans, goals?

Jean-François Lacombe: I haven't thought about what's next yet. First, I have to do the exposition at the Centre des Arts Contemporains. It's going to be more of an installation, a big, big installation, with lots of objects interacting with each other.

Zeke: So it's more than just The Eels?

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes. It's gonna be a narrative. Not just poetic pieces, but pieces that you can relate to, like, symbols, objects in it, and the interaction between these symbols and objects in space.

Zeke: We can get back to that later, but I'd like to discuss the environmental nature of your stuff. Where did it come from? How far back? When you were you four, when you were two?

Jean-François Lacombe: I always played outside. I was a lonely kid. There was this field. I was always playing with wood or stones. As far back as I can remember I always liked to build tree houses. I was always fascinated with the phenomena of life, the cycles, the cycles of the seasons. Beside the house there was this big ditch and right after that there was the rail road. In the spring, the ditch would fill with water, so I would build rafts. I remember one time, the ice broke and I fell in the cold water. It was strange to feel wet in the heart of winter. I'll remember it always... So I guess it goes back to that time.

Zeke: When you were there was the stuff you were building and playing around with anyway similar to what's up here now?

Jean-François Lacombe: Not at all. But, I could make a parallel or you could relate it to the imaginary world that I built then. I always try to build stuff that has history. I always try to build a history around the objects. A beginning, a middle, and an end. So you can sense the growing process. So yeah, I guess that's a similarity. This expo was a bit in reaction to what I was learning at school. I started out studying graphic design. It was the coming of the computer, everyone was jumping on the computer, letting go of drawing, of the materials. They were trying to deconstruct the letters, Ray Gun... and all that stuff. I wasn't into that. I don't know why. But I started building things and going to the workshop. Working with wood. And at that time I started going on what I called "lonely expeditions" In old warehouses on the Canal Lachine. I would pick up discarded objects that I could incorporate into my sculptures. I felt that there was a connection I was looking for a sort of past. Not just the presence of newness, but pieces that were weathered, that had lived for a while. Just like the material I used when I was little. For me, it was that connection I was looking for. The direct feelings of things. The experience of the phenomena, the natural cycles of things, including death. Not just to make them abstract or theory, but experience them for myself firsthand. I don't want to lose that connection, that intimacy with the elements.

Zeke: I notice with certain pieces, like most of The Lampas and Hieroglyph, that there is a sort of design element to them. However, with The Eels, they are very different. Where did that idea come from?

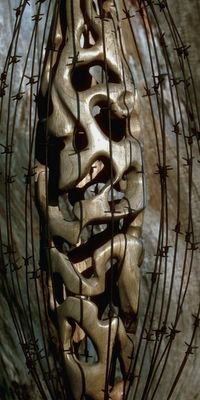

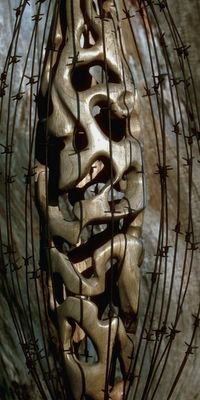

Hyéroglyphe

Jean-François Lacombe: The Eels were produced during my residency at Saint Jean Port Joli Centre Est Nord Est. The purpose of the residency is to create something in a new context. I wanted to go further than The Lampas. For me, The Lampas were something in the past. Something that I've dealt with. And I was trying to go beyond that. The Eels actually can be traced back to my ideas formed while making an earlier work. The Ephemeral sculpture for the University de Montreal. Which was a wall going through from the outside to the inside made out of recycled cedar. With this project I was trying to grasp the essence of the passage, the transition, inside outside, from one material to the other. I was very pleased with the result with the wood part. You can sense the strong sense of energy, of movement. So I tried to build on that with The Eels. The installation is meant to mimic or represent a wave. A sense of movement, but inside. Saint Jean Port Joli is a River front, the St. Lawrence. So the St. Lawrence river was a big influence, during my residency, because of the tides. That phenomena was very appealing to me. I tried to represent that in this installation.

Passage Ephemere

Zeke: I'm thinking in terms of one very specific difference, most of your other pieces are made out of multiple media. Wood and stone, or leaves. Metal and wood. The Eels are only made out of wood. Was that a conscious decision based out of the Ephemeral Passageway or did it just happen naturally?

Lampa X detail

Jean-François Lacombe: I had to work in a very short period of time with the materials I had and since Saint Jean Port Jolie has a big history of carving. It's known as, the cradle of the sculpture for Quebec, so I tried to work with that. And I also tried to incorporate some poetic work in a narrative context.

Zeke: OK. I'm thinking that if you don't suspend them and put them all on the ground as opposed to eels they'd be snakes.

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes [laughs].

Zeke: So when you wanna exhibit them some place like Arizona just call them "Snake Project."

Jean-François Lacombe: [laughs.]

Zeke: Um, I'm getting the idea that most of your work is very very thought intensive, and that you almost think them out entirely in the abstract before actually doing any of them. Is that the case?

Jean-François Lacombe: No [laughs]. Especially not "The Lampas" or my first works.

Zeke: That would surprise me, because I would think with the Lampas that seems like a lot of thought went into them, and obviously they're gonna be certain changes along the way, but that they almost come out almost fully formed and you say "OK, this are the objects I have, this is how I want to combine them."

Lampa XII detail

Jean-François Lacombe: Well, I imagine you could sense the lampas are designed because each piece was created for and from a specific site, and the stories that emerge from that place. But things are different from what I imagine at first... and the result... I don't think is always planned. 'Cause always, like you said, the randomness of the materials and the process, and the techniques that we have to work with, and the accidents... that play a big part of it. But yeah, I've always drawn things first. I have a specific idea. Sometime of the purpose of the sculpture...that's never explained. Ah, and then that feeling or that purpose becomes informed at the end.

Zeke: OK. Is there any piece that you've done where you've done the opposite in terms of not sketching, just saying, "Oh, this is a beautiful object, a beautiful material, let's jut see what happens"?

Jean-François Lacombe: "Yellow Flower."

Zeke: OK. So it's like just slit the bottom...

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes.

Zeke:...and then slip in the glass rods?.

Jean-François Lacombe: Indeed.

Zeke: OK, 'cause people have asked me if the holes were drilled and I said, "Nope!" [laughs]

Jean-François Lacombe: They are. [laughs]

Zeke: OK.

Jean-François Lacombe: But yeah, it was quite the opposite for process for me with this piece. And this piece makes the transition from "The Lampas" For the show at O Patro Vys. I didn't want to show stuff that I'd only made in the past. I wanted to make some new pieces. That was "The Yellow Flower."

Zeke: OK.

Jean-François Lacombe: I think I was just pleased with the process of it. Just getting back into the moment, directly into the material.

Zeke: OK. You were a little bit reticent about showing old stuff here, why?

Jean-François Lacombe: For two reasons. One is that, as you mentioned, "The Eels" and "The Lampas" are so different. I didn't want to create confusion.

Zeke: Uh huh. It is the certain thing where you take, say, "Meet the Beetles" and "Sergeant Pepper's", they don't sound anything alike, but they're made but the same people "I Wanna Hold Your Hand" is as good as "A Day in the Life" for different reasons, but there isn't anyone who would confuse the two. Though, there are certain people who say they like earlier Beatles more that later Beatles. But there isn't a sense of confusion, and it is the same with any artistic career, the sense of progress that in my mind...

Lampa XII

Jean-François Lacombe: Maybe this apprehension comes from the fact that I haven't done shows before. Over the past seven years, and this leap to new stuff. And frankly, the new stuff, by itself, just "Eels" like that, doesn't say much.

Zeke: . I agree, but there from my perspective, taking any one piece out of here would not hurt the show. But putting good stuff, definitely makes the show better. Then with "The Eels," they're sorta like a sub section.

Jean-François Lacombe: Um, what can I say? I... since these are narrative installations...that you will grasp the sense or the feeling...when you see the other objects and their position in space, it felt just weird to put it like that.

Zeke: OK.

Jean-François Lacombe: The Lampas are pieces that can hold on their own.

Zeke: Uh huh. In my mind "The Eels" while not as powerful as "The Lampas"...

Jean-François Lacombe: Alone.

Zeke:…are worthwhile objects on their own, and it is the sorta thing where you're imposing a certain narrative and meaning on them from your perspective. Someone else's perspective is not necessarily wrong, incorrect, they get something different, you can get into endless discussions, which are fascinating and fun.

Projet des Anguilles [aka The Eels]

Jean-François Lacombe: You mean the next installation?

Zeke: No, I'm talking in terms of in theory, the sort of thing where "The Eels" 'cause they're there, give you a specific idea in mind, somebody else comes in and says, "Oh, I have this idea from them, I get this sense from them." At which point, you can say, "That's not my idea," but it can't be wrong." At which point saying that they are a good sculpture, installation, and that somebody else gets something else from it.

[ed note: While editing this interview Jean-François wanted to stress this point by adding - "Indeed, the idea is not to impose a closed meaning upon the work, but to go beyond the unique object (Lampa) and to use both the space and the juxtaposition of different pieces to create layers of meaning, layers of possibilities, layers of stories."]

Zeke: There's also, in terms of my thinking, one theory I have in regards to Quebecois art or Canadian art, Quebecois art more specifically, you view the stuff you're doing as projects and there's a sense that once a project is done it gets retired. It's like your gong from the Jardin Botanique. You have no plans on what to do other than it's gonna gather dust for the next couple of years until you say "Enough of this, let's do something with it." And maybe it gets turned into another sculpture. Whereas in the States, in Europe, there is a whole sorta sense of "Yes, I am making specific projects, but they are designed as opposed to just being seen," sold, and seen multiple times. And getting you to get that sense, that it may be four years old, but hiding it in your studio and letting it gather dust is not a good idea.

Jean-François Lacombe: Yeah, the project, "The Eels" is meant to grow I think. 'Cause I did an installation back at Saint Jean Port Joli with them, but then exhibiting them at Centre des Arts Contemporain it becomes a totally different thing. But I'm using the same elements... I'm very involved right now with site specific projects. Using the space, using the atmosphere, the spirit of the place. This gives me the opportunity to work on a larger scale.

Zeke: In my mind it's like, had we suspended the gong, right here.

Jean-François Lacombe: We could have. [laughs] Of course.

Zeke: That's one of the things I adore about this place, just how the art is forced to interact with the place, even though it was never created for the space.

Installation Shot

Jean-François Lacombe: Well, with any interior space, that's the case, 'cause at the Centre des Arts Contemporains it's not gonna be white walls. I'm doing this in their basement. It's the old bricks and the dirt floor...

Zeke: If you need any help with the hanging let me know.

Jean-François Lacombe: OK, great. Thank you [laughs].

Zeke: Yeah, you say after the Centre des Arts Contemporains you have a proposal for the Jardin du Metis. What's the idea behind that project? Because I imagine that you've started sketching for it, do you have any ideas?

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes, it's a about transition again, transitional space.

Zeke: Are you going to work with metal, wood, stone...?

Jean-François Lacombe: Wood. Yes...almost just wood. Trees, you know?

Zeke: When you incorporate different materials, to me works way better. If you're planning on all just all wood - that transition to one material...

Jean-François Lacombe: It's not just a transition for, Jardin du Metis, or any project that's outside, you work with the vegetation, with the rocks, with the ground, with the air, with the water, so all these elements become a part of the project, a part of the sculpture. So with the Jardin du Metis, what I'm planning to do is incorporate stuff that would go in the ground, up the air, and you would have a movement, you would move through the space. I would like to use the trees also, and incorporate that with the elements of the... So it's not a unique material that I'm going to be using. But then again, it's just a proposal. But once a project appears to me, I have to push it all the way out, even if it's not materialized. I realize the mental process, so I can sorta go beyond it.

Zeke: OK, so that brings in another sort of thing: What artist's do you emulate, do you appreciate, do you think suck?

Jean-François Lacombe: I will start with the Quebecois, 'cause coming from the design schools, I didn't learn anything about sculpture, especially not sculptors from Quebec. So I've just discovered sculptors recently from Quebec. But Roland Poulin, not inspiration, but I admire his simplicity, and his installations, I would say. But the installation part of his work, there's always three or four balance, and this is like one piece. There's a strong sense of humanity and spirituality in his work that I relate to. Of course there's Andy Goldsworthy. When I started doing sculptures he was a great influence to just translate the phenomena into materiality. What others? What's his name, the Japanese guy? I could send it to you...he did some work with recyclables, wood planks. Always invading the space, I would say.

Zeke: Any artists that you don't like?

Jean-François Lacombe: [laughs] That I don't like? There's no I can think of...the ones that I like, I like very much, and all the others are like in the same bag, you know? If I can't relate to the work, if I'm not touched by it, I'm not interested in it, I won't go and read what it means. 'Cause if it don't touches me at first, I'm not interested. So I'm always trying to do this, to appeal to the senses, the sensuality, so you can relate to the pieces. And then, if there's an intellectual process afterwards. But, yeah, very conceptual artists I don't like, I don't relate to it, it's just, how do you say it rendre compte?

Zeke: Rendre Compte? I understand it but I'm not certain I can come up with the translation.

Jean-François Lacombe: The, ah, much of the contemporary work, well at least in Quebec, is much too rendre compte, of something that is going on. We say "Oh this is going on, so we present it." There's nothing - well there's not much work, that project you somewhere else. That say, OK, "This is going on, but what could happen next? Could we go somewhere else than this reality?"

Zeke: OK. I do find within Quebec, the artists are very insular. No one thinks outside the borders of Quebec.

Jean-François Lacombe: Indeed.

Zeke: Which I find unfortunate.

Jean-François Lacombe: Not as much at the centres d'artistes but the grant system encourages that. It's very much the statement of the artist, the progression of the artist regarding the past history of art that seems important to them, more relevant than the pieces themselves, which I find a bit problematic. It's hard for me to explain because I took the opposite route. The first sculpture I did was a commission, and I did a lot of those before considering doing any shows. I came into that world of sculpture to use my intuition rather than my intellect. So theorizing about my work is outside the essential essence of it.

Zeke: Yes. I like where Canada Council is in the process of revamping their whole grant structure, and I really, really like what they're doing. Although they're a whole lot of people complaining up the wazoo.

Jean-François Lacombe: Well, as you mentioned, the art market is absent in Quebec. This is one of the big reasons the conseil des arts works in the way they do. 'Cause people are not interested in buying art.

Zeke: No, but they could force people to become interested. And you can't forget here in Quebec, no one is developing a secondary market, either.

Jean-François Lacombe: No.

Zeke: And that's why I say with regards to your art, to then get you out of "these are my past, don't want to be dealing with them." No. This is foundation from which you build.

Jean-François Lacombe: But the other thing about the art world, in particular, the one percent for art that gets integrated with architecture and new buildings. In the process of it, the artist gets a lot of money.

Zeke: Well that depends, sometimes they don't get a lot.

Jean-François Lacombe: Well they get a lot of budget. I don't know if they get a lot of money in their pocket, that's another question [laughs]. But this process is more like... more people are involved, not just other artists, unlike when they give out grants. It's not just peers, the architect, some artists, the owner of the building, users and citizens. Many people get involved: they chose something, they chose an artist, they chose a piece. So this process is more an open process, I would say. A closed process would be the artist creating alone in is studio.

Zeke: Oh no, I disagree with you entirely. Look at, the Laval metro extension. The artist got $80,000, 1%, for art. However, they have cost overruns. So when the cost has gone up do they increase the 1%? No, they don't. The woman who is running the whole show has already said she wants, some sort of video stained glass type thing. So she's already got it fixed in her head what she wants. To my mind that closes the door right there. You could submit you stuff for that, but she's already said, "This is what I want." She running the project. The four people sitting around the table are gonna probably listen. You take, down at the Palais de Congres, the Pink Trees and the Pixilated Face. I don't like 'em, I won't ask you if you like it or not, but hello! And how do they incorporate it into the whole space? They look like they were plopped down. You take the Bibliotheque Nationale. They're putting the, the 1% art back out. Nobody's gonna see it. And to my mind, it is like, yeah, on the surface they're doing a good deed, but they really aren't doing anything other than giving lip service, saying, "Yeah, we gotta support art," and so on.

Jean-François Lacombe: But it is the same thing, the same process, as when you get a commission from a company. They have something in mind and you have to work around that to produce something that you can relate to. You necessarily have to make some concessions, even if it's just the material chosen. I separate the commission from my other work. Two ways of doing things, different but similar. I find that the 1% relates more to a design process than to sculpture.

Zeke: To my mind, you should stand it on its head and say, "OK. This is what I've made, 'Lampa X,' is what I've made. Now, what can I do to incite someone to buy it? What can I do so as to then make sure that the value increases?"

Jean-François Lacombe: You have to be a seller to do that.

Zeke: Yeah.

Jean-François Lacombe: And artists are not sellers.

Zeke: Oh, some of them are.

Jean-François Lacombe: Well that's good for them! But I'm not.

Zeke: And that's why galleries come in, auction houses come in, why there are other players. But in Quebec there isn't that sort of way of thinking. And so you gotta find it elsewhere. To take "Lampa IV," take all the "The Lampas," go down to New York- I'm certain it would be as easy as pie to get them in some gallery there. And at which point, you go and make a whole whack of new stuff. Take "The Eels," after it's at Centre d'Art Contemporain, there are how many other places that can do installations like that? Take that out on the road, sell them off one by one by one, and then you're good to go.

Lampa II

Jean-François Lacombe: What I meant by the process of the commission, there is some good and bad things about it. I don't know if it's possible to impose a piece on someone that has the power and makes the decision. The power? It's a big issue.

Zeke: Yeah, but you don't have to impose it on them, but you can focus their thinking saying, "OK. This is really pretty, this is what it's worth now, and given the state of the career, given the state of the stuff Jean-François Lacombe has made, this is what I can see in the future." And for somebody solely focused on money, that's one way to focus their thinking. For somebody who is solely focused on aesthetics, and doesn't think about the money aspect; "No, once I get an object, I dust it off everyday, I look at it, I gaze at it fondly, it makes my life happy" and so on. That's another way of thinking. Making people more aware, having as many as exhibitions as possible. All of those things can be done, both in concert and separately. And to my mind, it is a matter of just figuring out which ones are important, and then going and doing them.

Lampa I detail

Jean-François Lacombe: Yeah, 'cause I think we'll have a big problem in the future.

Zeke: Yep.

Jean-François Lacombe: Big problems. But that's another story.

Zeke: Your thesis was the last sort of major topic I wanted to discuss - can you explain it to me a little bit?

Jean-François Lacombe: [laughs] This came from the project I've did for my diploma. I wanted to find a place to show "The Lampas" - that was the goal, that was the original project. I found this old quarry I was going to...

Zeke: Would you like more beer as well?

Jean-François Lacombe: Sure.

Zeke: OK. Where was this quarry?

Jean-François Lacombe: near Melocheville. The thing with the quarry is there's lots of old concrete walls, concrete structures made to move the rocks. It's like a modern Stonehenge. They're all aligned in a certain way. The vegetation - 'cause it's a abandoned - just sprung out. There was a strong feeling and spirit to it, so I had difficulty integrating the pieces in it. This led me to just study and assimilate the essence that was in the quarry. So I went on with that project to do my Master's degree. What I found was there is always a physical landscape. So this is like the ground, the air, and the sunlight, the vegetation. And the other part of the spirit of the place is the imaginary landscape, what I call imaginary, but it's more like the projectoral or the intellectual, it's the memoire du lieu. Thought always requires both physical and imaginary landscape to be complete. It's the interaction between the two that produces the spirit, the meaning of the place, the sense of the place.

Zeke: Sounds very cool. If you've got a spare copy lying around or you want to email me one...

Jean-François Lacombe: OK, sure. I will. So that was the big wrap up of all the experiments I've done with the sculptures. Integrating them with the landscape, taking some material in situ, and then bringing back the sculptures and taking photographs of the sculptures in the landscape. Sometimes I refer to "The Lampas" as embodying that landscape. But with the installation, they don't embody a landscape, they create one. And maybe the thesis help me to separate those two, to be able to combine them more effectively.

Zeke: Yes, to recognize which is...

Jean-François Lacombe: Which is which, yeah. Which belongs to which, 'cause it's not always clear... like your yellow wall. When people came here, the wall, the yellow wall was a physical landscape, but the association you make with that wall is more intellectual, more a projection. What does it project? A white wall with no holes in it or a yellow wall with some holes in it? But the couch is still here, the beer is still here, what's the difference?

Topographie

Zeke: Yeah, it's why, one of the reasons were, when I could make the intellectual leap to say, "Yes, change is possible and I do have faith." But it wasn't until I said, "OK, I have faith." And now, having experienced the new space - the one thing that I'm most aware of - is that the space is not as bright, and that to me is a significant change.

Jean-François Lacombe: OK, yeah, maybe it's the green-

Zeke: - it's a dark green

Jean-François Lacombe: Yeah, but it's a nice color.

Zeke: OK, have you ever thought of incorporating sound as well into your installations?

Jean-François Lacombe: At the CACQM there's gonna be some sound and some projection.

Zeke: OK, video projection as well?

Jean-François Lacombe: We don't know yet. I have a friend who's a musician and composer. He did the soundtrack for my animation film, stop motion "Debacle." He did a good job so I might ask him to do it again.

Zeke: Are there any questions you'd like to ask?

Jean-François Lacombe: What about the show? What about the general feelings about the show?

Zeke: Oh, I like it very much. I recognize that this show is about as close to white cube as I ever want to get.

Jean-François Lacombe: Oh yeah?

Zeke: Yeah, it strikes me as being very white cube like, ie each piece has it's own space, it can be set off so it is contemplative, and to me- especially with the change in the paint job - it is the sort of thing where it is a little too neat and clean.

Lampa I

Jean-François Lacombe: OK [laughs].

Zeke: Nonetheless, it think the art is phenomenal, so it does make that sort of antiseptic edge less hard. I enjoy it very much, and if I didn't I, would not have pressured you so much into doing it.

Jean-François Lacombe: What about the vernisage and the comments you've had?

Zeke: The general commentary I've had is overwhelmingly not only positive but superlative. Everybody's said, "Whoa, this is cool." And I say, "Yes, you can touch it, you're not going to break it! They're heavy"

Jean-François Lacombe: [laughs] Yes, indeed.

Zeke: And just watching people as they interact with the stuff, whether they're coming in to do other business, and suddenly look around and say, "Whoa, that's cool." Or they come in totally expecting art in here, but their previous experiences with art here was about as radically different as you can imagine, and suddenly they're looking around, and saying, "Holy smokes, this is cool." With the vernisages, yeah, I was pissed off with the delays on the invitation. However in pure numbers I would have preferred way more, but, I think we ended up with about 160 odd people for the vernisages, so I figure that's alright, not great but alright.

Jean-François Lacombe: Yeah, that's good.

Zeke: I figure we'll probably end up with something like, I don't know, 1,000-1,500 people who will come through here during the course of the exhibition, which to my mind is very good.

Jean-François Lacombe: That's good. I like the multipurposeness of this gallery. I think this attracts many people, many different people. I think that's a good thing 'cause it's not just art lovers coming in, but people who are sensitive to art.

Zeke: That's why I'm so dead set against the white cube, 'cause it is sorta like how many people read Robbe-Grillet? However, you put him on Oprah's Book Club, people are gonna pick him up and say, "OK, yeah, cool." Most people in Quebec, and actually in my mind worldwide, think galleries are painful places to go into. I don't get it. They shouldn't be. To turn them into warm, inviting, open places. These things don't bite. But it's the sorta thing, you come, you look, and so OK, you don't like it, bamn, you walk out, no skin off of my back, no skin off of yours. That's why there's the crossover between the music, the poetry, the couches, the beer.

Lampa X

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes, indeed. And I have to say I had some positive comments about you.

Zeke: Well, thank you.

Jean-François Lacombe: And it's a good thing. They said you were very dynamic, and enthusiastic about the show, so yeah, it was a fun experience. It's not over yet, so that's good. I've liked the vernisages. I think that's a good idea too. And it's very important to get the feedback from people, to hear that people come, and get something out of the piece, and to hear what they get out of it. It's interesting 'cause it's always something you hadn't thought about.

Zeke: I find that difficult, 'cause I'm the gallery guy. I invariably set up a situation where I'm the one telling them what I think. So it is the sort of thing where I can foam at the mouth about any of these pieces.

Jean-François Lacombe: You can what?

Zeke: Foam at the mouth. Basically go on, talk for half and hour, go on about the dynamism of the sticks as they go from fat to skinny, in term of the connections between the verticality and horizontality, yet they're framed and stuff like that. However, although wood is a very light object 'casue it floats on water they're stuck in friggin' concrete! That sucker is 750 Goddamn pounds! [laughs] and riff off of that, so I very rarely hear other people's reactions. If you can talk long and wax eloquent about the latest U2 album, you can do the same thing about visual art.

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes.

Zeke: Same terminology too.

Jean-François Lacombe: But they have to be in contact with it.

Zeke: Yes, exactly, that's why I say experience it. It's the sort of thing where somebody who spends their evenings watching TV. Suddenly their TV. busts? They will pick up a book. Someone doesn't have a TV., they're gonna read lots. If you give them... if you set them up in a way so that they can experience stuff, that's great.

Jean-François Lacombe: But it's frightening at first, for them. I mean it's... my cousin came. She never went to a exhibition before, an art show before. She said, "I don't know what to wear, I don't know what to say."

Zeke: Tell her "Put on a t-shirt and some jeans!"

Jean-François Lacombe: What's the dress code tonight? [laughs] But their perception of art is deeply changed.

Zeke: I agree, and that's why, in a gallery setting, I'm doing my best to shift all of those perceptions.

Jean-François Lacombe: Alright.

Zeke: OK. Anything else?

Jean-François Lacombe: I think that's it.

Zeke: OK. Thank you very, very much.

Back at the end of 2004 during Jean-François Lacombe's exhibit here I interviewed him. It has finally been transcribed by Jacquline Mabey, who I thank ever so much for her help. All of the photos were taken by Paul Litherland, unless they were taken by Jean-François.

If you'd like more information about Jean-François Lacombe's work click here, or here.

Zeke: First, what do you think about the show? Don't pull any punches.

Jean-François Lacombe: Qu'est ce que tu veux dire? [What do you mean?]

Zeke: Don't hold back anything.

Jean-François Lacombe: I'm pleased about it. I'm pleased with the changes you made. I'm very pleased with the effort. The only problem is the invitations. I would have hoped that they could have been sent out earlier.

Zeke: Yeah, I agree.

Jean-François Lacombe: There would have been more people at the event. But I'm also happy about the vernisage because there were lots of people who I didn't know.

Zeke: OK. What do you have as far as plans for the future?

Jean-François Lacombe: I'm going to be applying to the Jardin de Metis. And that's a big step for me. That's the direction I'd like to go. I want to continue sculpting pieces, small pieces, for inside, in gallery. But, this would be more an interactive work, a site-specific work. And, since there's about a hundred thousand people that visit the Jardin de Metis every year it's a nice opportunity. And since it's a garden, I can interact with nature.

Installation Shot from Above, Below, Center and Ether

Zeke: And beyond that? Do you have any ideas, plans, goals?

Jean-François Lacombe: I haven't thought about what's next yet. First, I have to do the exposition at the Centre des Arts Contemporains. It's going to be more of an installation, a big, big installation, with lots of objects interacting with each other.

Zeke: So it's more than just The Eels?

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes. It's gonna be a narrative. Not just poetic pieces, but pieces that you can relate to, like, symbols, objects in it, and the interaction between these symbols and objects in space.

Zeke: We can get back to that later, but I'd like to discuss the environmental nature of your stuff. Where did it come from? How far back? When you were you four, when you were two?

Jean-François Lacombe: I always played outside. I was a lonely kid. There was this field. I was always playing with wood or stones. As far back as I can remember I always liked to build tree houses. I was always fascinated with the phenomena of life, the cycles, the cycles of the seasons. Beside the house there was this big ditch and right after that there was the rail road. In the spring, the ditch would fill with water, so I would build rafts. I remember one time, the ice broke and I fell in the cold water. It was strange to feel wet in the heart of winter. I'll remember it always... So I guess it goes back to that time.

Zeke: When you were there was the stuff you were building and playing around with anyway similar to what's up here now?

Jean-François Lacombe: Not at all. But, I could make a parallel or you could relate it to the imaginary world that I built then. I always try to build stuff that has history. I always try to build a history around the objects. A beginning, a middle, and an end. So you can sense the growing process. So yeah, I guess that's a similarity. This expo was a bit in reaction to what I was learning at school. I started out studying graphic design. It was the coming of the computer, everyone was jumping on the computer, letting go of drawing, of the materials. They were trying to deconstruct the letters, Ray Gun... and all that stuff. I wasn't into that. I don't know why. But I started building things and going to the workshop. Working with wood. And at that time I started going on what I called "lonely expeditions" In old warehouses on the Canal Lachine. I would pick up discarded objects that I could incorporate into my sculptures. I felt that there was a connection I was looking for a sort of past. Not just the presence of newness, but pieces that were weathered, that had lived for a while. Just like the material I used when I was little. For me, it was that connection I was looking for. The direct feelings of things. The experience of the phenomena, the natural cycles of things, including death. Not just to make them abstract or theory, but experience them for myself firsthand. I don't want to lose that connection, that intimacy with the elements.

Zeke: I notice with certain pieces, like most of The Lampas and Hieroglyph, that there is a sort of design element to them. However, with The Eels, they are very different. Where did that idea come from?

Hyéroglyphe

Jean-François Lacombe: The Eels were produced during my residency at Saint Jean Port Joli Centre Est Nord Est. The purpose of the residency is to create something in a new context. I wanted to go further than The Lampas. For me, The Lampas were something in the past. Something that I've dealt with. And I was trying to go beyond that. The Eels actually can be traced back to my ideas formed while making an earlier work. The Ephemeral sculpture for the University de Montreal. Which was a wall going through from the outside to the inside made out of recycled cedar. With this project I was trying to grasp the essence of the passage, the transition, inside outside, from one material to the other. I was very pleased with the result with the wood part. You can sense the strong sense of energy, of movement. So I tried to build on that with The Eels. The installation is meant to mimic or represent a wave. A sense of movement, but inside. Saint Jean Port Joli is a River front, the St. Lawrence. So the St. Lawrence river was a big influence, during my residency, because of the tides. That phenomena was very appealing to me. I tried to represent that in this installation.

Passage Ephemere

Zeke: I'm thinking in terms of one very specific difference, most of your other pieces are made out of multiple media. Wood and stone, or leaves. Metal and wood. The Eels are only made out of wood. Was that a conscious decision based out of the Ephemeral Passageway or did it just happen naturally?

Lampa X detail

Jean-François Lacombe: I had to work in a very short period of time with the materials I had and since Saint Jean Port Jolie has a big history of carving. It's known as, the cradle of the sculpture for Quebec, so I tried to work with that. And I also tried to incorporate some poetic work in a narrative context.

Zeke: OK. I'm thinking that if you don't suspend them and put them all on the ground as opposed to eels they'd be snakes.

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes [laughs].

Zeke: So when you wanna exhibit them some place like Arizona just call them "Snake Project."

Jean-François Lacombe: [laughs.]

Zeke: Um, I'm getting the idea that most of your work is very very thought intensive, and that you almost think them out entirely in the abstract before actually doing any of them. Is that the case?

Jean-François Lacombe: No [laughs]. Especially not "The Lampas" or my first works.

Zeke: That would surprise me, because I would think with the Lampas that seems like a lot of thought went into them, and obviously they're gonna be certain changes along the way, but that they almost come out almost fully formed and you say "OK, this are the objects I have, this is how I want to combine them."

Lampa XII detail

Jean-François Lacombe: Well, I imagine you could sense the lampas are designed because each piece was created for and from a specific site, and the stories that emerge from that place. But things are different from what I imagine at first... and the result... I don't think is always planned. 'Cause always, like you said, the randomness of the materials and the process, and the techniques that we have to work with, and the accidents... that play a big part of it. But yeah, I've always drawn things first. I have a specific idea. Sometime of the purpose of the sculpture...that's never explained. Ah, and then that feeling or that purpose becomes informed at the end.

Zeke: OK. Is there any piece that you've done where you've done the opposite in terms of not sketching, just saying, "Oh, this is a beautiful object, a beautiful material, let's jut see what happens"?

Jean-François Lacombe: "Yellow Flower."

Zeke: OK. So it's like just slit the bottom...

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes.

Zeke:...and then slip in the glass rods?.

Jean-François Lacombe: Indeed.

Zeke: OK, 'cause people have asked me if the holes were drilled and I said, "Nope!" [laughs]

Jean-François Lacombe: They are. [laughs]

Zeke: OK.

Jean-François Lacombe: But yeah, it was quite the opposite for process for me with this piece. And this piece makes the transition from "The Lampas" For the show at O Patro Vys. I didn't want to show stuff that I'd only made in the past. I wanted to make some new pieces. That was "The Yellow Flower."

Zeke: OK.

Jean-François Lacombe: I think I was just pleased with the process of it. Just getting back into the moment, directly into the material.

Zeke: OK. You were a little bit reticent about showing old stuff here, why?

Jean-François Lacombe: For two reasons. One is that, as you mentioned, "The Eels" and "The Lampas" are so different. I didn't want to create confusion.

Zeke: Uh huh. It is the certain thing where you take, say, "Meet the Beetles" and "Sergeant Pepper's", they don't sound anything alike, but they're made but the same people "I Wanna Hold Your Hand" is as good as "A Day in the Life" for different reasons, but there isn't anyone who would confuse the two. Though, there are certain people who say they like earlier Beatles more that later Beatles. But there isn't a sense of confusion, and it is the same with any artistic career, the sense of progress that in my mind...

Lampa XII

Jean-François Lacombe: Maybe this apprehension comes from the fact that I haven't done shows before. Over the past seven years, and this leap to new stuff. And frankly, the new stuff, by itself, just "Eels" like that, doesn't say much.

Zeke: . I agree, but there from my perspective, taking any one piece out of here would not hurt the show. But putting good stuff, definitely makes the show better. Then with "The Eels," they're sorta like a sub section.

Jean-François Lacombe: Um, what can I say? I... since these are narrative installations...that you will grasp the sense or the feeling...when you see the other objects and their position in space, it felt just weird to put it like that.

Zeke: OK.

Jean-François Lacombe: The Lampas are pieces that can hold on their own.

Zeke: Uh huh. In my mind "The Eels" while not as powerful as "The Lampas"...

Jean-François Lacombe: Alone.

Zeke:…are worthwhile objects on their own, and it is the sorta thing where you're imposing a certain narrative and meaning on them from your perspective. Someone else's perspective is not necessarily wrong, incorrect, they get something different, you can get into endless discussions, which are fascinating and fun.

Projet des Anguilles [aka The Eels]

Jean-François Lacombe: You mean the next installation?

Zeke: No, I'm talking in terms of in theory, the sort of thing where "The Eels" 'cause they're there, give you a specific idea in mind, somebody else comes in and says, "Oh, I have this idea from them, I get this sense from them." At which point, you can say, "That's not my idea," but it can't be wrong." At which point saying that they are a good sculpture, installation, and that somebody else gets something else from it.

[ed note: While editing this interview Jean-François wanted to stress this point by adding - "Indeed, the idea is not to impose a closed meaning upon the work, but to go beyond the unique object (Lampa) and to use both the space and the juxtaposition of different pieces to create layers of meaning, layers of possibilities, layers of stories."]

Zeke: There's also, in terms of my thinking, one theory I have in regards to Quebecois art or Canadian art, Quebecois art more specifically, you view the stuff you're doing as projects and there's a sense that once a project is done it gets retired. It's like your gong from the Jardin Botanique. You have no plans on what to do other than it's gonna gather dust for the next couple of years until you say "Enough of this, let's do something with it." And maybe it gets turned into another sculpture. Whereas in the States, in Europe, there is a whole sorta sense of "Yes, I am making specific projects, but they are designed as opposed to just being seen," sold, and seen multiple times. And getting you to get that sense, that it may be four years old, but hiding it in your studio and letting it gather dust is not a good idea.

Jean-François Lacombe: Yeah, the project, "The Eels" is meant to grow I think. 'Cause I did an installation back at Saint Jean Port Joli with them, but then exhibiting them at Centre des Arts Contemporain it becomes a totally different thing. But I'm using the same elements... I'm very involved right now with site specific projects. Using the space, using the atmosphere, the spirit of the place. This gives me the opportunity to work on a larger scale.

Zeke: In my mind it's like, had we suspended the gong, right here.

Jean-François Lacombe: We could have. [laughs] Of course.

Zeke: That's one of the things I adore about this place, just how the art is forced to interact with the place, even though it was never created for the space.

Installation Shot

Jean-François Lacombe: Well, with any interior space, that's the case, 'cause at the Centre des Arts Contemporains it's not gonna be white walls. I'm doing this in their basement. It's the old bricks and the dirt floor...

Zeke: If you need any help with the hanging let me know.

Jean-François Lacombe: OK, great. Thank you [laughs].

Zeke: Yeah, you say after the Centre des Arts Contemporains you have a proposal for the Jardin du Metis. What's the idea behind that project? Because I imagine that you've started sketching for it, do you have any ideas?

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes, it's a about transition again, transitional space.

Zeke: Are you going to work with metal, wood, stone...?

Jean-François Lacombe: Wood. Yes...almost just wood. Trees, you know?

Zeke: When you incorporate different materials, to me works way better. If you're planning on all just all wood - that transition to one material...

Jean-François Lacombe: It's not just a transition for, Jardin du Metis, or any project that's outside, you work with the vegetation, with the rocks, with the ground, with the air, with the water, so all these elements become a part of the project, a part of the sculpture. So with the Jardin du Metis, what I'm planning to do is incorporate stuff that would go in the ground, up the air, and you would have a movement, you would move through the space. I would like to use the trees also, and incorporate that with the elements of the... So it's not a unique material that I'm going to be using. But then again, it's just a proposal. But once a project appears to me, I have to push it all the way out, even if it's not materialized. I realize the mental process, so I can sorta go beyond it.

Zeke: OK, so that brings in another sort of thing: What artist's do you emulate, do you appreciate, do you think suck?

Jean-François Lacombe: I will start with the Quebecois, 'cause coming from the design schools, I didn't learn anything about sculpture, especially not sculptors from Quebec. So I've just discovered sculptors recently from Quebec. But Roland Poulin, not inspiration, but I admire his simplicity, and his installations, I would say. But the installation part of his work, there's always three or four balance, and this is like one piece. There's a strong sense of humanity and spirituality in his work that I relate to. Of course there's Andy Goldsworthy. When I started doing sculptures he was a great influence to just translate the phenomena into materiality. What others? What's his name, the Japanese guy? I could send it to you...he did some work with recyclables, wood planks. Always invading the space, I would say.

Zeke: Any artists that you don't like?

Jean-François Lacombe: [laughs] That I don't like? There's no I can think of...the ones that I like, I like very much, and all the others are like in the same bag, you know? If I can't relate to the work, if I'm not touched by it, I'm not interested in it, I won't go and read what it means. 'Cause if it don't touches me at first, I'm not interested. So I'm always trying to do this, to appeal to the senses, the sensuality, so you can relate to the pieces. And then, if there's an intellectual process afterwards. But, yeah, very conceptual artists I don't like, I don't relate to it, it's just, how do you say it rendre compte?

Zeke: Rendre Compte? I understand it but I'm not certain I can come up with the translation.

Jean-François Lacombe: The, ah, much of the contemporary work, well at least in Quebec, is much too rendre compte, of something that is going on. We say "Oh this is going on, so we present it." There's nothing - well there's not much work, that project you somewhere else. That say, OK, "This is going on, but what could happen next? Could we go somewhere else than this reality?"

Zeke: OK. I do find within Quebec, the artists are very insular. No one thinks outside the borders of Quebec.

Jean-François Lacombe: Indeed.

Zeke: Which I find unfortunate.

Jean-François Lacombe: Not as much at the centres d'artistes but the grant system encourages that. It's very much the statement of the artist, the progression of the artist regarding the past history of art that seems important to them, more relevant than the pieces themselves, which I find a bit problematic. It's hard for me to explain because I took the opposite route. The first sculpture I did was a commission, and I did a lot of those before considering doing any shows. I came into that world of sculpture to use my intuition rather than my intellect. So theorizing about my work is outside the essential essence of it.

Zeke: Yes. I like where Canada Council is in the process of revamping their whole grant structure, and I really, really like what they're doing. Although they're a whole lot of people complaining up the wazoo.

Jean-François Lacombe: Well, as you mentioned, the art market is absent in Quebec. This is one of the big reasons the conseil des arts works in the way they do. 'Cause people are not interested in buying art.

Zeke: No, but they could force people to become interested. And you can't forget here in Quebec, no one is developing a secondary market, either.

Jean-François Lacombe: No.

Zeke: And that's why I say with regards to your art, to then get you out of "these are my past, don't want to be dealing with them." No. This is foundation from which you build.

Jean-François Lacombe: But the other thing about the art world, in particular, the one percent for art that gets integrated with architecture and new buildings. In the process of it, the artist gets a lot of money.

Zeke: Well that depends, sometimes they don't get a lot.

Jean-François Lacombe: Well they get a lot of budget. I don't know if they get a lot of money in their pocket, that's another question [laughs]. But this process is more like... more people are involved, not just other artists, unlike when they give out grants. It's not just peers, the architect, some artists, the owner of the building, users and citizens. Many people get involved: they chose something, they chose an artist, they chose a piece. So this process is more an open process, I would say. A closed process would be the artist creating alone in is studio.

Zeke: Oh no, I disagree with you entirely. Look at, the Laval metro extension. The artist got $80,000, 1%, for art. However, they have cost overruns. So when the cost has gone up do they increase the 1%? No, they don't. The woman who is running the whole show has already said she wants, some sort of video stained glass type thing. So she's already got it fixed in her head what she wants. To my mind that closes the door right there. You could submit you stuff for that, but she's already said, "This is what I want." She running the project. The four people sitting around the table are gonna probably listen. You take, down at the Palais de Congres, the Pink Trees and the Pixilated Face. I don't like 'em, I won't ask you if you like it or not, but hello! And how do they incorporate it into the whole space? They look like they were plopped down. You take the Bibliotheque Nationale. They're putting the, the 1% art back out. Nobody's gonna see it. And to my mind, it is like, yeah, on the surface they're doing a good deed, but they really aren't doing anything other than giving lip service, saying, "Yeah, we gotta support art," and so on.

Jean-François Lacombe: But it is the same thing, the same process, as when you get a commission from a company. They have something in mind and you have to work around that to produce something that you can relate to. You necessarily have to make some concessions, even if it's just the material chosen. I separate the commission from my other work. Two ways of doing things, different but similar. I find that the 1% relates more to a design process than to sculpture.

Zeke: To my mind, you should stand it on its head and say, "OK. This is what I've made, 'Lampa X,' is what I've made. Now, what can I do to incite someone to buy it? What can I do so as to then make sure that the value increases?"

Jean-François Lacombe: You have to be a seller to do that.

Zeke: Yeah.

Jean-François Lacombe: And artists are not sellers.

Zeke: Oh, some of them are.

Jean-François Lacombe: Well that's good for them! But I'm not.

Zeke: And that's why galleries come in, auction houses come in, why there are other players. But in Quebec there isn't that sort of way of thinking. And so you gotta find it elsewhere. To take "Lampa IV," take all the "The Lampas," go down to New York- I'm certain it would be as easy as pie to get them in some gallery there. And at which point, you go and make a whole whack of new stuff. Take "The Eels," after it's at Centre d'Art Contemporain, there are how many other places that can do installations like that? Take that out on the road, sell them off one by one by one, and then you're good to go.

Lampa II

Jean-François Lacombe: What I meant by the process of the commission, there is some good and bad things about it. I don't know if it's possible to impose a piece on someone that has the power and makes the decision. The power? It's a big issue.

Zeke: Yeah, but you don't have to impose it on them, but you can focus their thinking saying, "OK. This is really pretty, this is what it's worth now, and given the state of the career, given the state of the stuff Jean-François Lacombe has made, this is what I can see in the future." And for somebody solely focused on money, that's one way to focus their thinking. For somebody who is solely focused on aesthetics, and doesn't think about the money aspect; "No, once I get an object, I dust it off everyday, I look at it, I gaze at it fondly, it makes my life happy" and so on. That's another way of thinking. Making people more aware, having as many as exhibitions as possible. All of those things can be done, both in concert and separately. And to my mind, it is a matter of just figuring out which ones are important, and then going and doing them.

Lampa I detail

Jean-François Lacombe: Yeah, 'cause I think we'll have a big problem in the future.

Zeke: Yep.

Jean-François Lacombe: Big problems. But that's another story.

Zeke: Your thesis was the last sort of major topic I wanted to discuss - can you explain it to me a little bit?

Jean-François Lacombe: [laughs] This came from the project I've did for my diploma. I wanted to find a place to show "The Lampas" - that was the goal, that was the original project. I found this old quarry I was going to...

Zeke: Would you like more beer as well?

Jean-François Lacombe: Sure.

Zeke: OK. Where was this quarry?

Jean-François Lacombe: near Melocheville. The thing with the quarry is there's lots of old concrete walls, concrete structures made to move the rocks. It's like a modern Stonehenge. They're all aligned in a certain way. The vegetation - 'cause it's a abandoned - just sprung out. There was a strong feeling and spirit to it, so I had difficulty integrating the pieces in it. This led me to just study and assimilate the essence that was in the quarry. So I went on with that project to do my Master's degree. What I found was there is always a physical landscape. So this is like the ground, the air, and the sunlight, the vegetation. And the other part of the spirit of the place is the imaginary landscape, what I call imaginary, but it's more like the projectoral or the intellectual, it's the memoire du lieu. Thought always requires both physical and imaginary landscape to be complete. It's the interaction between the two that produces the spirit, the meaning of the place, the sense of the place.

Zeke: Sounds very cool. If you've got a spare copy lying around or you want to email me one...

Jean-François Lacombe: OK, sure. I will. So that was the big wrap up of all the experiments I've done with the sculptures. Integrating them with the landscape, taking some material in situ, and then bringing back the sculptures and taking photographs of the sculptures in the landscape. Sometimes I refer to "The Lampas" as embodying that landscape. But with the installation, they don't embody a landscape, they create one. And maybe the thesis help me to separate those two, to be able to combine them more effectively.

Zeke: Yes, to recognize which is...

Jean-François Lacombe: Which is which, yeah. Which belongs to which, 'cause it's not always clear... like your yellow wall. When people came here, the wall, the yellow wall was a physical landscape, but the association you make with that wall is more intellectual, more a projection. What does it project? A white wall with no holes in it or a yellow wall with some holes in it? But the couch is still here, the beer is still here, what's the difference?

Topographie

Zeke: Yeah, it's why, one of the reasons were, when I could make the intellectual leap to say, "Yes, change is possible and I do have faith." But it wasn't until I said, "OK, I have faith." And now, having experienced the new space - the one thing that I'm most aware of - is that the space is not as bright, and that to me is a significant change.

Jean-François Lacombe: OK, yeah, maybe it's the green-

Zeke: - it's a dark green

Jean-François Lacombe: Yeah, but it's a nice color.

Zeke: OK, have you ever thought of incorporating sound as well into your installations?

Jean-François Lacombe: At the CACQM there's gonna be some sound and some projection.

Zeke: OK, video projection as well?

Jean-François Lacombe: We don't know yet. I have a friend who's a musician and composer. He did the soundtrack for my animation film, stop motion "Debacle." He did a good job so I might ask him to do it again.

Zeke: Are there any questions you'd like to ask?

Jean-François Lacombe: What about the show? What about the general feelings about the show?

Zeke: Oh, I like it very much. I recognize that this show is about as close to white cube as I ever want to get.

Jean-François Lacombe: Oh yeah?

Zeke: Yeah, it strikes me as being very white cube like, ie each piece has it's own space, it can be set off so it is contemplative, and to me- especially with the change in the paint job - it is the sort of thing where it is a little too neat and clean.

Lampa I

Jean-François Lacombe: OK [laughs].

Zeke: Nonetheless, it think the art is phenomenal, so it does make that sort of antiseptic edge less hard. I enjoy it very much, and if I didn't I, would not have pressured you so much into doing it.

Jean-François Lacombe: What about the vernisage and the comments you've had?

Zeke: The general commentary I've had is overwhelmingly not only positive but superlative. Everybody's said, "Whoa, this is cool." And I say, "Yes, you can touch it, you're not going to break it! They're heavy"

Jean-François Lacombe: [laughs] Yes, indeed.

Zeke: And just watching people as they interact with the stuff, whether they're coming in to do other business, and suddenly look around and say, "Whoa, that's cool." Or they come in totally expecting art in here, but their previous experiences with art here was about as radically different as you can imagine, and suddenly they're looking around, and saying, "Holy smokes, this is cool." With the vernisages, yeah, I was pissed off with the delays on the invitation. However in pure numbers I would have preferred way more, but, I think we ended up with about 160 odd people for the vernisages, so I figure that's alright, not great but alright.

Jean-François Lacombe: Yeah, that's good.

Zeke: I figure we'll probably end up with something like, I don't know, 1,000-1,500 people who will come through here during the course of the exhibition, which to my mind is very good.

Jean-François Lacombe: That's good. I like the multipurposeness of this gallery. I think this attracts many people, many different people. I think that's a good thing 'cause it's not just art lovers coming in, but people who are sensitive to art.

Zeke: That's why I'm so dead set against the white cube, 'cause it is sorta like how many people read Robbe-Grillet? However, you put him on Oprah's Book Club, people are gonna pick him up and say, "OK, yeah, cool." Most people in Quebec, and actually in my mind worldwide, think galleries are painful places to go into. I don't get it. They shouldn't be. To turn them into warm, inviting, open places. These things don't bite. But it's the sorta thing, you come, you look, and so OK, you don't like it, bamn, you walk out, no skin off of my back, no skin off of yours. That's why there's the crossover between the music, the poetry, the couches, the beer.

Lampa X

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes, indeed. And I have to say I had some positive comments about you.

Zeke: Well, thank you.

Jean-François Lacombe: And it's a good thing. They said you were very dynamic, and enthusiastic about the show, so yeah, it was a fun experience. It's not over yet, so that's good. I've liked the vernisages. I think that's a good idea too. And it's very important to get the feedback from people, to hear that people come, and get something out of the piece, and to hear what they get out of it. It's interesting 'cause it's always something you hadn't thought about.

Zeke: I find that difficult, 'cause I'm the gallery guy. I invariably set up a situation where I'm the one telling them what I think. So it is the sort of thing where I can foam at the mouth about any of these pieces.

Jean-François Lacombe: You can what?

Zeke: Foam at the mouth. Basically go on, talk for half and hour, go on about the dynamism of the sticks as they go from fat to skinny, in term of the connections between the verticality and horizontality, yet they're framed and stuff like that. However, although wood is a very light object 'casue it floats on water they're stuck in friggin' concrete! That sucker is 750 Goddamn pounds! [laughs] and riff off of that, so I very rarely hear other people's reactions. If you can talk long and wax eloquent about the latest U2 album, you can do the same thing about visual art.

Jean-François Lacombe: Yes.

Zeke: Same terminology too.

Jean-François Lacombe: But they have to be in contact with it.

Zeke: Yes, exactly, that's why I say experience it. It's the sort of thing where somebody who spends their evenings watching TV. Suddenly their TV. busts? They will pick up a book. Someone doesn't have a TV., they're gonna read lots. If you give them... if you set them up in a way so that they can experience stuff, that's great.

Jean-François Lacombe: But it's frightening at first, for them. I mean it's... my cousin came. She never went to a exhibition before, an art show before. She said, "I don't know what to wear, I don't know what to say."

Zeke: Tell her "Put on a t-shirt and some jeans!"

Jean-François Lacombe: What's the dress code tonight? [laughs] But their perception of art is deeply changed.

Zeke: I agree, and that's why, in a gallery setting, I'm doing my best to shift all of those perceptions.

Jean-François Lacombe: Alright.

Zeke: OK. Anything else?

Jean-François Lacombe: I think that's it.

Zeke: OK. Thank you very, very much.

<< Home